By Susanne Argamaso Maher

Schools make convenient settings for testing youth-oriented universal-level programs. There is a ready-made population and trainable program facilitators already in place. Getting those programs in place can sometimes be more difficult – schools are bombarded with solicitations, and program purveyors must become salespersons to compete against the growing number of available curricula claiming to fix the wide range of problems schools can practically touch they are so real. It is easier to “sell” programs that have been proven, through rigorous testing in controlled or real world environments, to work. These programs integrate well into the established school agenda and don’t create high response cost for teaching staff. The story of one program, PATHS (Promoting Alternative THinking Strategies) is one of success, and hope for the successful development of the students who are attending the schools where it is being implemented.

“When reviewing their survey results, all of the schools acknowledged concerns with the level of responses reporting elevated mental health issues among their students, including emotional symptoms, as well as peer and conduct problems. ”

Promoting Alternative THinking Strategies is an elementary school-based universal-level social and emotional learning program that was developed to help students build social and emotional competencies, and reduce childhood aggression and behavior problems while providing for an enhanced educational experience in the classroom. The program targets five major conceptual domains, including self-control, emotional understanding, positive self-esteem, relationships, and interpersonal problem solving skills. Trained classroom teachers use a scripted curriculum with corresponding school and home activities to reinforce the lesson material. Core elements of program implementation include facilitator training, support from school administrators and program facilitators, and full implementation of all program components (lessons completed sequentially twice a week and required activities).

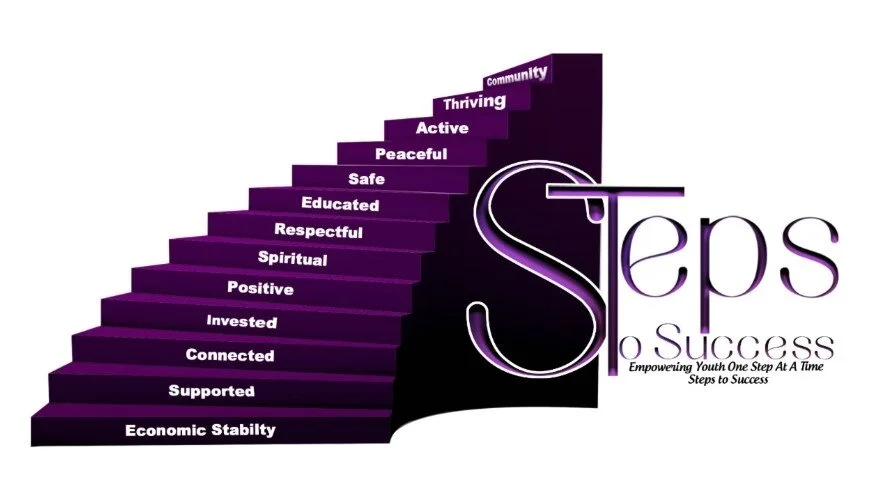

The PATHS implementation is part of a larger initiative locally known in Denver’s Montbello neighborhood as Steps to Success. A number of Montbello schools completed school climate surveys in the Spring and Fall of 2012. This survey identifies the strengths and challenges in the school climate, as well as other risk and protective factors for violence and anti-social behavior. Data from these surveys and a community survey of Montbello youth aged 10-17 and their parents was presented to a community board comprised of members of the Montbello community and city-level stakeholders who are invested in positive youth development. The board then prioritized the risk and protective factors that were most important to address in order to reduce problem behaviors and increase positive behaviors in Montbello youth. While the bulk of the target population for the project were middle and high school students, the board felt very strongly about directing resources to prevention efforts at the younger ages. They chose the PATHS program as a universal, school-based program because of the concern about the mental health of the children in the neighborhood, and because of the strong, demonstrated effects of the program in building social and emotional competencies in children.

The elementary schools that completed the school climate survey were approached in Spring 2013 about implementing PATHS. When reviewing their survey results, all of the schools acknowledged concerns with the level of responses reporting elevated mental health issues among their students, including emotional symptoms, as well as peer and conduct problems. The schools were presented with the opportunity to receive training, materials, and technical assistance for the PATHS program as part of the research project, and three of the schools accepted the offer. Due to funding constraints, it was determined to pilot the program in one grade (third) and gradually build out the implementation, adding one grade at a time in each subsequent year of the project.

Ideally, when introducing a new program into a school setting, teachers are involved in the decision-making process. After all, they will be the primary program facilitators, and if they are not educated on and bought into the benefits of the program, they can consciously or inadvertently sabotage the implementation by not staying true to the program model, which includes attending full training and “following the script,” that is, implementing all components of the program as they were designed to be presented. In Montbello, due to the timing of the release of the survey results, prioritization of risk and protective factors, and determination and approval of the evidence-based program package, school meetings were not able to be scheduled until close to the end of the school year, when it was not possible to schedule meetings to include teachers. School administrators assured project staff that they had obtained teacher buy-in for the program before dispersing for the summer.

PATHS training occurs over two non-consecutive days, where teachers are introduced to the program, its theoretical rationale and outcomes, and begin to see the program in action through demonstration of the lesson material. The first training date ideally occurs prior to the beginning of school, so that teachers can begin to implement program components and set the tone for the program as soon as school starts, with the second training day following 6-9 weeks later, after the program has been put into practice. There, teachers can celebrate implementation successes as well as address challenges experienced before delving into the second half of the curriculum.

For the three schools in Montbello initiating PATHS in the Fall of 2013, it became clear at the outset of the training that teachers were largely unaware of this new curriculum placed in their care, much less when and how they were going to implement it. Several of the teachers were brand new to their schools, and not all of the participants were aware of the concept of social emotional learning. To their credit, the training participants were open minded to the training process, receptive to the trainer, and approached the practice activities with an enthusiasm that left them feeling confident in their ability to deliver the program with fidelity. They were also amenable to the requirement to undergo program monitoring and participate in a process evaluation for the purposes of the research project. Program monitors also attended the training to understand how the program was to be implemented and to put the teachers at ease with their presence in the classroom.

In order to build administrative support around PATHS, the trainer returned to Denver to meet with school principals to review the research and core components of the program, and to provide materials on ways they could support their teachers through implementation. PATHS-specific research has shown that higher levels of administrator support result in stronger implementation quality, both in implementing lessons and generalizing PATHS concepts (Ransford et al., 2009; Kam, Greenberg & Walls, 2003).

Research protocols required a process evaluation for all implemented programs. Implementing evidence-based programs are predicted to result in anticipated demonstrated results as long as the program is implemented with faithfulness to the model, or fidelity. A process evaluation is conducted to measure this level of fidelity. Multiple reporting methods are employed to strengthen the results of the process evaluation. For this project, two reporting methods were used, third party program monitoring and program facilitator interviews and feedback. Program monitors were hired by the project to be a neutral presence in the classroom and observe PATHS lessons in progress. They conducted five unannounced observations per teacher over the course of implementation using a prescribed monitoring form that rated the teachers’ ability to both teach the PATHS-specific program components and generalize the PATHS concepts to create an environment for social and emotional learning.

“observations indicated that teachers were successfully able to generalize the program concepts in their classrooms, and there was a high level of engagement from students participating in the program. ”

According to the observation data collected, teachers did an excellent job implementing the program with fidelity in their first year teaching PATHS. Program monitors indicated faithfulness to the program, with an overall adherence rate of 97% across teachers and schools. Additionally, observations indicated that teachers were successfully able to generalize the program concepts in their classrooms, and there was a high level of engagement from students participating in the program. Observation data was backed up by interviews of teachers and administrators, who felt the program was relevant, interesting, and valuable to students, both in expanding their vocabulary and having a positive impact on general behavior. Finally, post-implementation feedback from teachers was good, with teachers indicating program effectiveness in improving student behavior directly targeted by the curriculum. They also felt supported by their school administrators in their implementation.

During the mid-year process evaluation visit (conducted February 2014), school administrators expressed a strong desire to expand implementation school-wide in the upcoming school year. They were getting positive reports from their teachers about the program in third grade and seeing subtle shifts in the behavior of the participating students. Above all, they were looking to see the program as a climate changing initiative, with consistent language and messaging around social emotional learning across grades.

The funding was found to support whole school implementation in the second year across all three schools. Two of the schools trained additional support staff (specials teachers, student services and administrative staff), and one of those schools provided two staff to receive extra training to become PATHS coaches. The PATHS coaches will be able to provide additional technical assistance to teachers throughout their implementation and provide workshops for parent involvement with the program. A fourth school trained their social workers to provide limited PATHS implementation to students (as a pull-out or on a classroom basis).

Whole-school implementation of the PATHS program has not come without its challenges. The varying demands of the academic programs at each grade level put constraints on teachers’ abilities to implement the program faithfully to the model. The schools in this area also have the added challenge of implementing an English-language based curriculum to a large Spanish-speaking population, particularly in the lower grades. While the take-home materials are provided in dual languages, the in-class curriculum is not. The schools are working through these issues, and with time and practice, should become more comfortable incorporating PATHS as part of the way the school conducts its business. They have access to resources that could help them improve their implementation through the end of grant funding.

“However, training new teachers (due to staff turnover) and replacing curriculum materials is expensive, and schools in this area are cash strapped, and cannot place the burden on families through PTO support. ”

All of the schools are looking to the future in their implementation of PATHS once research funding ends in 2016. They seem committed to embedding the program into the fabric of their schools to support social and emotional competences in their students, and to align with the Denver Plan 2020, which charges Denver Public Schools (DPS) with creating school environments that provide “support for the whole child “. However, training new teachers (due to staff turnover) and replacing curriculum materials is expensive, and schools in this area are cash strapped, and cannot place the burden on families through PTO support. There are a few options, both at the school and district levels that will be explored to help fill the void left when grant funding ends. These options include working with schools early to determine the possibility of working maintenance costs into annual budgeting, increasing visibility and support for the program through parent and community engagement activities, and developing local trainers through the PATHS Affiliate Trainer Program, to provide the district with a more cost efficient resource for providing training to current and future schools within DPS. Schools will have access to their individual school and aggregate reports to assist them when seeking outside funding support. Possible expansion within DPS might also shift the financial burden for program costs to the district. It is the responsibility of the research project to leave a legacy behind for the youth of Montbello to have ongoing access to the best tools available to positively develop successful futures. Program champions will need to be identified within the schools or district to move implementation forward.

“the community should take tremendous credit for the progress made to date and the commitment to their youth in encouraging positive youth development. ”

However the future implementation of PATHS in Montbello proceeds, the community should take tremendous credit for the progress made to date and the commitment to their youth in encouraging positive youth development. The schools are to be commended for accepting the responsibility of faithful program implementation born out of a desire to improve the lives and futures of their students. And the families in Montbello are acknowledged for embracing the possibilities made available to them to assist them in creating a pathway for success for their children.

References:

Kam, C. M., Greenberg, M. T., & Walls, C. T. (2003). Examining the role of implementation quality in school-based prevention using the PATHS curriculum, Prevention Science, 4, 55-63.

Ransford, C. R., Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Small, M., & Jacobson, L. (2009). The role of teachers' psychological experiences and perceptions of curriculum supports on the implementation of a social and emotional learning curriculum. School Psychology Review, 38(4), 510.